I began this blog with a poem by Mahmoud Darwish, Palestine's national poet. I thought it only right, in keeping with my concern for balance and equality, to end my blog with a poem by the celebrated Israeli poet Rachel. (Plus, the choice of these two poets has the added value of being gender-balanced too.)

By now, I am back home, but my mind is still reeling with thoughts of Israel and Palestine. Rachel's poem reflects both the humble and passionate origins of the land, as well as its pervasive sadness. I've also included links to two interviews, one with a Palestinian poet and one with an Israeli. For me, where politics and policy fail, in poetry lies answers beyond reason or dogma. It is to the hidden truth of poetry that we must finally turn - not to agonizingly parsed peace treaties or quid pro quo agreements. Through conflict, we must learn to trust the guiding compass of our conscience and the universality of the human creed.

To My Country

I have not sung to you, my country,

not brought glory to your name

with the great deeds of a hero

or the spoils a battle yields.

But on the shores of the Jordan

my hands have planted a tree,

and my feet have made a pathway

through your fields.

Modest are the gifts I bring you.

I know this, mother.

Modest, I know, the offerings

of your daughter:

Only an outburst of song

on a day when the light flares up,

only a silent tear

for your poverty.

- Rachel

"For Palestinians, Identity Is Regained Through Poetry": http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/entertainment/jan-june07/poetry_03-22.html

Israeli Poetry Reflects Story of a Nation: http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/entertainment/jan-june07/poetry_03-21.html

(P.S. In case you didn't notice - all my blog entries until this one were titled with questions. By the end, I felt entitled to one answer, or at least a declarative statement...)

Saturday, August 1, 2009

Thursday, July 30, 2009

Where Did My School Go?

In Amman now, I feel I should be reflecting on the entirety of the past two months, its scope, impact, personal meaning. But at the moment, sleep-deprived and sun-stroked, I feel that all I can muster is to describe a small but significant moment that happened to me a few days before leaving.

I had met an old school friend, someone I hadn’t seen in over seven years. We both used to live in Haifa and commuted daily to the American International School in Kfar Shemaryahu, right outside Herzliya and near Tel Aviv. Before I left Israel in 2002, AIS administration was in the process of purchasing land for a new school near Netanya. Recently completed and now fully operational, the new AIS is supposed to be quite a grand campus, dotted with tennis courts and a swimming pool in addition to other academic and recreational facilities. I was not able to visit, but from an old math teacher I heard that while the physical amenities are new and expansive, the old spirit is missing. Of course, this is the sad byproduct of change – what you gain in appearance and efficacy, sometimes you loose in ambiance and warmth.

Still, it was not the new school that concerned me, but the old. I asked my friend if we could drive by the old campus in Kfar Shemaryahu, for old time’s sake. She warned me I would be shocked. She warned me what to expect, but still I was unprepared for the sting.

Everything, every building, bench and bathroom had been completely removed. All that remained of the old AIS were the two rusty blue gates, one leading in from the bus lot, the other leading to the main entrance. The rest was overgrown weeds, a few trees, dirt piles, brambles. “That was the North Field, remember?” my friend pointed sadly. “And that was where the Kiosk was, where we used to eat lunch.”

As we sat in her car, we conjured the school as we had known it. Before our eyes, we saw the squished classrooms, the added trailers where no new classrooms could be erected, the gymnasium where I had captained the Middle School Hockey Marathon, the High School corridor, the open-air quad…

Suddenly, in the midst of our reveries and recollections, I turned to my friend and said, “So, now I know what it feels to be Palestinian.” My friend, an Israeli citizen, laughed at first, but let me go on with my extrapolation. For me, seeing the place where so many memories, good and bad, had been made, where I had spent three incredible, growth-laden years – seeing that place destroyed was to me a revelation. And it was only three years of my life! My old math teacher had taught there for 30 years. Palestinians have been in Israel for generations. The twinge I felt was an intimation, albeit slight, of what must have been the shocking devastation of being violently uprooted and then subsequently erased.

I must note, however, that this realization not only applies to my greater empathy for the Palestinians, but also for the Jews. By the end of this trip, I have shored up my initial assertion of balance with reading, observation and analysis. I now feel compelled to include both Israelis and Palestinians in statements of support but also of critique. Perhaps by this subtle interposition, I can somehow contribute to the imperative of rapprochement.

I had met an old school friend, someone I hadn’t seen in over seven years. We both used to live in Haifa and commuted daily to the American International School in Kfar Shemaryahu, right outside Herzliya and near Tel Aviv. Before I left Israel in 2002, AIS administration was in the process of purchasing land for a new school near Netanya. Recently completed and now fully operational, the new AIS is supposed to be quite a grand campus, dotted with tennis courts and a swimming pool in addition to other academic and recreational facilities. I was not able to visit, but from an old math teacher I heard that while the physical amenities are new and expansive, the old spirit is missing. Of course, this is the sad byproduct of change – what you gain in appearance and efficacy, sometimes you loose in ambiance and warmth.

Still, it was not the new school that concerned me, but the old. I asked my friend if we could drive by the old campus in Kfar Shemaryahu, for old time’s sake. She warned me I would be shocked. She warned me what to expect, but still I was unprepared for the sting.

Everything, every building, bench and bathroom had been completely removed. All that remained of the old AIS were the two rusty blue gates, one leading in from the bus lot, the other leading to the main entrance. The rest was overgrown weeds, a few trees, dirt piles, brambles. “That was the North Field, remember?” my friend pointed sadly. “And that was where the Kiosk was, where we used to eat lunch.”

As we sat in her car, we conjured the school as we had known it. Before our eyes, we saw the squished classrooms, the added trailers where no new classrooms could be erected, the gymnasium where I had captained the Middle School Hockey Marathon, the High School corridor, the open-air quad…

Suddenly, in the midst of our reveries and recollections, I turned to my friend and said, “So, now I know what it feels to be Palestinian.” My friend, an Israeli citizen, laughed at first, but let me go on with my extrapolation. For me, seeing the place where so many memories, good and bad, had been made, where I had spent three incredible, growth-laden years – seeing that place destroyed was to me a revelation. And it was only three years of my life! My old math teacher had taught there for 30 years. Palestinians have been in Israel for generations. The twinge I felt was an intimation, albeit slight, of what must have been the shocking devastation of being violently uprooted and then subsequently erased.

I must note, however, that this realization not only applies to my greater empathy for the Palestinians, but also for the Jews. By the end of this trip, I have shored up my initial assertion of balance with reading, observation and analysis. I now feel compelled to include both Israelis and Palestinians in statements of support but also of critique. Perhaps by this subtle interposition, I can somehow contribute to the imperative of rapprochement.

Saturday, July 25, 2009

Friday, July 24, 2009

War Zone or Comfort Zone?

My last internship visit was to the Geneva Initiative, a non-governmental organization that “provides realistic and achievable solutions on all issues [related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict], based on previous official negotiations, international resolutions, the Quartet Roadmap, Clinton Parameters, Bush Vision, and Arab Peace Initiative.” This according to their mission statement. My roommate was primarily involved in revamping their English-language website (http://www.geneva-accord.org), as well as coordinating operations with the Palestinian office.

Interestingly, the Palestine office is not called “Geneva Initiative – Palestine” but rather the “Palestinian Peace Coalition.” When I asked one of her coworkers about the name disparity, he gave a thorough (though unofficial) rationale. Apparently, in some polls, Palestinians given a comprehensive peace agreement resembling the Geneva Accord but called something else are generally favorable to the approach. When given the same agreement under the name “Geneva Accord,” the favorability decreases significantly. It seems that the foreign-sounding name, along with the relationship to European and US benefactors, is distasteful to many Palestinians. Also, although both Arafat and Abu Mazen (Mahmoud Abbas) supported much of the substance of the Geneva Accord, they couldn’t officially state their support since doing so would compromise their initial bargaining stance, leaving them no fallback position.

This same coworker also mentioned that although no Palestinian leader has been brave enough to confront their public’s wishful thinking about the “right of return,” Arafat did attempt indirectly replace the refugee issue with the promise of Jerusalem. Since it is more likely that part of Jerusalem will come under Palestinian sovereignty than it is that Israel will allow a return of all refugees displaced in 1948 (which, frankly, will never happen), Arafat was attempting to shift his public’s expectations and also their priorities. In all his public appearances, Arafat repeated three times “Jerusalem al-Quds” or “Jerusalem the Holy.” It was the issue of Jerusalem that sank the Camp David talks of July 2000, not the right of return. In the Geneva Accord, Israel must absorb some number of refugees, equivalent in proportion to the average accepted by other third countries. However, the exact number is up to the Israeli state to determine. The fact is that no comprehensive refugee return policy can coexist with the reality of Israel as a Jewish state. The two concepts are mutually exclusive.

The Accord also stipulates that Jerusalem would be divided, with the Christian, Muslim and parts of the Armenian Quarters coming under Palestinian sovereignty, and the Jewish Quarter and other parts of the Armenian Quarter to be left in Israeli hands. Palestinians would also gain the right to fly their flag on the Haram al-Sharif, or Temple Mount, where the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque are located. The main document of the Geneva Accord can’t be more than 50 pages (the Annexes, as yet unpublished, run into the hundreds). I’ve read it, and, as anyone will tell you, there are no real surprises or innovations. It is roughly based on the Clinton Parameters of 2000, a short document (all of two pages), that provided the basic ingredients of a compromised peace.

I say “compromised peace” intentionally, for it will not be a true compromise, a good-faith give-and-take. Rather, both parties will be morally compromised by whatever political agreement is eventually hashed out. Why do I say this? Because the situation as it now stands only lends itself to cold peace (i.e. a formal one without cultural interaction), a cessation of hostilities maybe, but not a true restitution of life. I spoke in an earlier entry about the lack of imagination on both sides. But the capacity for imagination is more than the invention of new and better peace deals. Its true value lies as a mechanism for becoming more self-aware by becoming less self-centered. Imagination cultivates empathy because it lets us truly inhabit, albeit virtually, another mode of living, another set of circumstances, trials and triumphs. Without imagination there is no empathy, and without empathy there is no peace. I’ve waited a long time to bring up empathy. It’s a trait I consider vital to the human experience, but it’s also one (along with compassion, conscience, courage, etc.) that can be overused and lose its core value.

Going to the Geneva Initiative was not my first experience with the “peace industry,” as they call it here. But it did drive home for me just how much conflict and peace – cold peace, cessation of hostilities – feed off each other, reinforce each other, and, ultimately, defeat each other. There is a fatigue among the activists I’ve met, and (I would assume) among the politicians and militants too. A fatigue and a fear. “What will we do if there actually is peace? Where will my retirement pension go?” the activists ask, half-joking. Conflict and the broken promise of peace are the norm here, and humans are creatures of habit. The faculty of imagination requires practice and here it is dulled by decades of disuse. I’ve said before that this is a land of paradoxes, but for me this is the greatest: In addition to a war zone, this conflict is a comfort zone, a place where two people maintain an unsustainable status quo, killing themselves slowly while fighting for the right to exist.

Interestingly, the Palestine office is not called “Geneva Initiative – Palestine” but rather the “Palestinian Peace Coalition.” When I asked one of her coworkers about the name disparity, he gave a thorough (though unofficial) rationale. Apparently, in some polls, Palestinians given a comprehensive peace agreement resembling the Geneva Accord but called something else are generally favorable to the approach. When given the same agreement under the name “Geneva Accord,” the favorability decreases significantly. It seems that the foreign-sounding name, along with the relationship to European and US benefactors, is distasteful to many Palestinians. Also, although both Arafat and Abu Mazen (Mahmoud Abbas) supported much of the substance of the Geneva Accord, they couldn’t officially state their support since doing so would compromise their initial bargaining stance, leaving them no fallback position.

This same coworker also mentioned that although no Palestinian leader has been brave enough to confront their public’s wishful thinking about the “right of return,” Arafat did attempt indirectly replace the refugee issue with the promise of Jerusalem. Since it is more likely that part of Jerusalem will come under Palestinian sovereignty than it is that Israel will allow a return of all refugees displaced in 1948 (which, frankly, will never happen), Arafat was attempting to shift his public’s expectations and also their priorities. In all his public appearances, Arafat repeated three times “Jerusalem al-Quds” or “Jerusalem the Holy.” It was the issue of Jerusalem that sank the Camp David talks of July 2000, not the right of return. In the Geneva Accord, Israel must absorb some number of refugees, equivalent in proportion to the average accepted by other third countries. However, the exact number is up to the Israeli state to determine. The fact is that no comprehensive refugee return policy can coexist with the reality of Israel as a Jewish state. The two concepts are mutually exclusive.

The Accord also stipulates that Jerusalem would be divided, with the Christian, Muslim and parts of the Armenian Quarters coming under Palestinian sovereignty, and the Jewish Quarter and other parts of the Armenian Quarter to be left in Israeli hands. Palestinians would also gain the right to fly their flag on the Haram al-Sharif, or Temple Mount, where the Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque are located. The main document of the Geneva Accord can’t be more than 50 pages (the Annexes, as yet unpublished, run into the hundreds). I’ve read it, and, as anyone will tell you, there are no real surprises or innovations. It is roughly based on the Clinton Parameters of 2000, a short document (all of two pages), that provided the basic ingredients of a compromised peace.

I say “compromised peace” intentionally, for it will not be a true compromise, a good-faith give-and-take. Rather, both parties will be morally compromised by whatever political agreement is eventually hashed out. Why do I say this? Because the situation as it now stands only lends itself to cold peace (i.e. a formal one without cultural interaction), a cessation of hostilities maybe, but not a true restitution of life. I spoke in an earlier entry about the lack of imagination on both sides. But the capacity for imagination is more than the invention of new and better peace deals. Its true value lies as a mechanism for becoming more self-aware by becoming less self-centered. Imagination cultivates empathy because it lets us truly inhabit, albeit virtually, another mode of living, another set of circumstances, trials and triumphs. Without imagination there is no empathy, and without empathy there is no peace. I’ve waited a long time to bring up empathy. It’s a trait I consider vital to the human experience, but it’s also one (along with compassion, conscience, courage, etc.) that can be overused and lose its core value.

Going to the Geneva Initiative was not my first experience with the “peace industry,” as they call it here. But it did drive home for me just how much conflict and peace – cold peace, cessation of hostilities – feed off each other, reinforce each other, and, ultimately, defeat each other. There is a fatigue among the activists I’ve met, and (I would assume) among the politicians and militants too. A fatigue and a fear. “What will we do if there actually is peace? Where will my retirement pension go?” the activists ask, half-joking. Conflict and the broken promise of peace are the norm here, and humans are creatures of habit. The faculty of imagination requires practice and here it is dulled by decades of disuse. I’ve said before that this is a land of paradoxes, but for me this is the greatest: In addition to a war zone, this conflict is a comfort zone, a place where two people maintain an unsustainable status quo, killing themselves slowly while fighting for the right to exist.

Thursday, July 23, 2009

Where Do They Stand?

I spoke in my last entry about “taking a stand” toward ourselves. I can’t take credit for the concept, which comes from Viktor Frankl’s incredibly perceptive works on psychology. Frankl, however, is speaking about taking a stand toward personal suffering – i.e. if someone has an incurable illness, he still can find meaning by the attitude he takes and the purpose he finds. I am speaking about taking a stand toward communal suffering – i.e. how we can each be responsible for our societies by being responsible for ourselves. Earlier I spoke in general about this necessary reorientation. What about its specific application to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict?

From what I’ve experienced firsthand, both sides are eager to shirk responsibility, to pawn off their own weaknesses as faults of the other side. I talk to Israelis and they bemoan the Palestinian lack of leadership, the fact that there’s “no one to talk to” on the other side, at least no one of equivalent position or expertise. Palestinians decry the Occupation, the Wall, the Oppression. It is difficult to find anyone willing to talk about the flaws and defects of their own society, the fact that Israelis are often complacent and content with the status quo – to the detriment of their moral authority – and the fact that Palestinians are either too invested in absolutes or else too fragmented to push for fair compromise. There are many, many more aspects in both cultures where introspection and self-critique are needed. The “New Historians” have begun this process in Israel, and Rashid Khalidi is starting the conversation in Palestinian academic circles, but these reflective and analytic voices are too few to generate generational change.

The philosopher Karl Jaspers once said, “What man is, he has become through a cause which he has made his own.” If we accept the truth of this statement, consider it in light of Israel/Palestine. The individuals of these respective societies have become who they are mainly by adopting the cause of conflict. Fighting for something (a state, recognition, land) or fighting against something (occupation, injustice, terrorism) – both come to the same end. People become so preoccupied with the “other” that they ironically become less self-aware and more self-centered. They loose one of the essential human freedoms: the freedom of imagination. They can no longer imagine what it is like to live an existence or to accept a truth contrary to their own. And since they can no longer imagine, they can no longer legitimize or empathize. I feel that when it comes to Israel/Palestine, both societies have lost this fundamental imaginative freedom.

This loss is felt everywhere, especially when the subject of peace is broached. I’ve talked to several Israeli students – well-schooled, well-traveled, intellectually curious and politically moderate youth – who all come to the same basic conclusion: There can be no peace. At best there will be a stand-off; at worst Israel will continue to build settlements and Palestinians will continue to blow themselves up. Why should Israel make any concessions with the current Palestinian “government”? When it comes to a “two-state solution” both sides – with the notable exception of officialdom – are incredulous. The one-state solution is only championed by a very few Palestinian academics and free-thinkers. A three-state solution is the domain of cynics. And what else is there?

This is where imagination would be so very helpful. Maybe instead of peace conferences and commissions and committees, we need some peace brainstorming, some peace blasphemy (what about giving social and financial incentives to Israeli-Palestinian interracial couples?). We need some risk-taking and political incorrectness. The hopelessness and complacency must be shaken up.

As I write this entry, I am sitting in a park on the bank of the Yarkon River. This sounds very picturesque, and, for Israel, it is. I mean, it’s hot and dusty and there are insects and power plants and the river is polluted…but…there are also families, birds singing, rowers, joggers, and birthday parties. Why should Israelis in such a place give two snaps for a Palestinian family in the West Bank or Gaza? Why should they care about the identity crisis facing Palestinian citizens of Israel? Moral arguments are not good enough, not when human satisfaction and security are at stake. Netanyahu’s “economic peace” is certainly part of the picture, for economic interdependence is one of the established pillars of Kant’s democratic peace theory (the idea that democracies don’t fight each other). But for Kant’s theory to work, both societies need to be democracies – and at the moment, one is (approximately) and one isn’t.

New stakes need to be created. King Abdullah of Jordan’s idea of the Arab Peace Initiative (that if a two-state solution is enacted, Israel would obtain official peace with all signatory Arab governments) is a generous though sadly empty offer. You see, Israel doesn’t really need peace with the other Arab states. It has peace with Jordan and Egypt, the two most influential. Economic stakes are important, but again, a greater incentive for Palestinians than for Israelis. Some Palestinian activists have attempted a “boycott, divest, and sanction” (BDS) movement around the world against the Israeli government. It’s too weak and support for Israel too strong. International condemnation of settlements and human rights abuses generally goes unnoticed. If normalized relations won’t work, and economics won’t work, and politics won’t work, and moral arguments won’t work, what will? Short of a heightened crisis (Intifada III? God forbid) or environmental catastrophe, it seems the only hope I can find is in the following:

• A SPIRITUAL EXCAVATION of the Holy Land to find the roots of the conflict, the true identity of the people. This undertaking must be individual as much as it is communal

• Personal and collective RESPONSIBILITY-TAKING

• Exercising the FREEDOM OF IMAGINATION to begin breaking down externally-shaped identities and creating internally-conscious (and conscientious) individuals

• As much COLLABORATION, co-education, and meaningful contact between the two sides as possible

• A transition, on both sides, from living in a state of SURVIVAL to one of EXISTENCE

• Much later, CO-EXISTENCE will be possible, but only after each side learns to live with themselves in a constructive way instead of the present destructive mentality

From what I’ve experienced firsthand, both sides are eager to shirk responsibility, to pawn off their own weaknesses as faults of the other side. I talk to Israelis and they bemoan the Palestinian lack of leadership, the fact that there’s “no one to talk to” on the other side, at least no one of equivalent position or expertise. Palestinians decry the Occupation, the Wall, the Oppression. It is difficult to find anyone willing to talk about the flaws and defects of their own society, the fact that Israelis are often complacent and content with the status quo – to the detriment of their moral authority – and the fact that Palestinians are either too invested in absolutes or else too fragmented to push for fair compromise. There are many, many more aspects in both cultures where introspection and self-critique are needed. The “New Historians” have begun this process in Israel, and Rashid Khalidi is starting the conversation in Palestinian academic circles, but these reflective and analytic voices are too few to generate generational change.

The philosopher Karl Jaspers once said, “What man is, he has become through a cause which he has made his own.” If we accept the truth of this statement, consider it in light of Israel/Palestine. The individuals of these respective societies have become who they are mainly by adopting the cause of conflict. Fighting for something (a state, recognition, land) or fighting against something (occupation, injustice, terrorism) – both come to the same end. People become so preoccupied with the “other” that they ironically become less self-aware and more self-centered. They loose one of the essential human freedoms: the freedom of imagination. They can no longer imagine what it is like to live an existence or to accept a truth contrary to their own. And since they can no longer imagine, they can no longer legitimize or empathize. I feel that when it comes to Israel/Palestine, both societies have lost this fundamental imaginative freedom.

This loss is felt everywhere, especially when the subject of peace is broached. I’ve talked to several Israeli students – well-schooled, well-traveled, intellectually curious and politically moderate youth – who all come to the same basic conclusion: There can be no peace. At best there will be a stand-off; at worst Israel will continue to build settlements and Palestinians will continue to blow themselves up. Why should Israel make any concessions with the current Palestinian “government”? When it comes to a “two-state solution” both sides – with the notable exception of officialdom – are incredulous. The one-state solution is only championed by a very few Palestinian academics and free-thinkers. A three-state solution is the domain of cynics. And what else is there?

This is where imagination would be so very helpful. Maybe instead of peace conferences and commissions and committees, we need some peace brainstorming, some peace blasphemy (what about giving social and financial incentives to Israeli-Palestinian interracial couples?). We need some risk-taking and political incorrectness. The hopelessness and complacency must be shaken up.

As I write this entry, I am sitting in a park on the bank of the Yarkon River. This sounds very picturesque, and, for Israel, it is. I mean, it’s hot and dusty and there are insects and power plants and the river is polluted…but…there are also families, birds singing, rowers, joggers, and birthday parties. Why should Israelis in such a place give two snaps for a Palestinian family in the West Bank or Gaza? Why should they care about the identity crisis facing Palestinian citizens of Israel? Moral arguments are not good enough, not when human satisfaction and security are at stake. Netanyahu’s “economic peace” is certainly part of the picture, for economic interdependence is one of the established pillars of Kant’s democratic peace theory (the idea that democracies don’t fight each other). But for Kant’s theory to work, both societies need to be democracies – and at the moment, one is (approximately) and one isn’t.

New stakes need to be created. King Abdullah of Jordan’s idea of the Arab Peace Initiative (that if a two-state solution is enacted, Israel would obtain official peace with all signatory Arab governments) is a generous though sadly empty offer. You see, Israel doesn’t really need peace with the other Arab states. It has peace with Jordan and Egypt, the two most influential. Economic stakes are important, but again, a greater incentive for Palestinians than for Israelis. Some Palestinian activists have attempted a “boycott, divest, and sanction” (BDS) movement around the world against the Israeli government. It’s too weak and support for Israel too strong. International condemnation of settlements and human rights abuses generally goes unnoticed. If normalized relations won’t work, and economics won’t work, and politics won’t work, and moral arguments won’t work, what will? Short of a heightened crisis (Intifada III? God forbid) or environmental catastrophe, it seems the only hope I can find is in the following:

• A SPIRITUAL EXCAVATION of the Holy Land to find the roots of the conflict, the true identity of the people. This undertaking must be individual as much as it is communal

• Personal and collective RESPONSIBILITY-TAKING

• Exercising the FREEDOM OF IMAGINATION to begin breaking down externally-shaped identities and creating internally-conscious (and conscientious) individuals

• As much COLLABORATION, co-education, and meaningful contact between the two sides as possible

• A transition, on both sides, from living in a state of SURVIVAL to one of EXISTENCE

• Much later, CO-EXISTENCE will be possible, but only after each side learns to live with themselves in a constructive way instead of the present destructive mentality

Monday, July 20, 2009

Where Do We Stand?

While living in Tel Aviv, I realized that this peace of mind is sorely lacking in one of Israel’s most vibrant cities. Oddly, while enjoying the pleasures of the city (galleries, music, the beach, shops), in Tel Aviv I feel more uncomfortable and conflicted than anywhere else in either Israel or the West Bank. For all its pretense at peace, I feel the least peaceful here. It is a place permanently at odds with its true identity. Tel Aviv pretends to be Miami Beach or southern France, a carefree, freewheeling hub of hipsters and bohemians, urban princesses and punks. “What conflict?” is the common, slightly tongue-in-cheek response I get to my persistent probing. Being an ostrich and living with one’s head in the sand is a false and ultimately defeatist way to find peace. It leads to just as much passivity and denial as that the Palestinian refugees who refuse to leave their camps.

Indeed, the parallels between West Bank refugees and Tel Aviv urbanites are striking. Both believe in a glorified and air-brushed past. For Palestinians, it is their rose-hued remembrance of land and family and freedom fighters, lost cities and lost brethren whose names become incantations. For Tel Avivers, it is their identification as “sabras” – strong, independent, land-loving Jews with a flair for military bravura and triumphant patriotism. Both refugees and Tel Avivers have constructed false walls around themselves. In the former case, refugees have perpetuated a false imprisonment in their now defunct camps. In reality, they are freer and more empowered than they know. In the latter case, Tel Avivers (and those Israelis who prefer separation to unease), have built a real Wall, a “security fence” that allows them the false liberation of their beaches and nightclubs. In reality, of course, they are more conflicted and less independent of the conflict than they admit.

Generally, then, I take away from this trip, and from my contrasting experiences in both Israel and the West Bank, a feeling of paradox. And, strangely enough, I am relieved at this outcome. Humans are always trying to flee “cognitive dissonance,” to pursue a worldview in which everything is simpatico and harmonized. But conflict is a part of life!

I don’t believe in “conflict resolution,” but rather “conflict transformation.” Conflict is natural but can either be destructive – as is the current case in Israel/Palestine – or constructive. Changing this conflict from destructive to constructive is the real challenge I see.

In the final analysis, what I found in Israel is a land of relics. A fossilized land of churches and icons, mosques and synagogues, pilgrims and tourists all jumbled together in confusion and lost meaning. Meaning must be regained or else conflict is inevitable. A new orientation, or reorientation, is needed. It’s time we take a stand. But this time, the stand we take should not be toward a person, cause, or ideal. That’s valuable, of course, but it misses our current crisis which is not outer, but inner in scope. It’s time for us to take responsibility.

It’s time we take a stand toward ourselves.

(To be continued...)

Indeed, the parallels between West Bank refugees and Tel Aviv urbanites are striking. Both believe in a glorified and air-brushed past. For Palestinians, it is their rose-hued remembrance of land and family and freedom fighters, lost cities and lost brethren whose names become incantations. For Tel Avivers, it is their identification as “sabras” – strong, independent, land-loving Jews with a flair for military bravura and triumphant patriotism. Both refugees and Tel Avivers have constructed false walls around themselves. In the former case, refugees have perpetuated a false imprisonment in their now defunct camps. In reality, they are freer and more empowered than they know. In the latter case, Tel Avivers (and those Israelis who prefer separation to unease), have built a real Wall, a “security fence” that allows them the false liberation of their beaches and nightclubs. In reality, of course, they are more conflicted and less independent of the conflict than they admit.

Generally, then, I take away from this trip, and from my contrasting experiences in both Israel and the West Bank, a feeling of paradox. And, strangely enough, I am relieved at this outcome. Humans are always trying to flee “cognitive dissonance,” to pursue a worldview in which everything is simpatico and harmonized. But conflict is a part of life!

I don’t believe in “conflict resolution,” but rather “conflict transformation.” Conflict is natural but can either be destructive – as is the current case in Israel/Palestine – or constructive. Changing this conflict from destructive to constructive is the real challenge I see.

In the final analysis, what I found in Israel is a land of relics. A fossilized land of churches and icons, mosques and synagogues, pilgrims and tourists all jumbled together in confusion and lost meaning. Meaning must be regained or else conflict is inevitable. A new orientation, or reorientation, is needed. It’s time we take a stand. But this time, the stand we take should not be toward a person, cause, or ideal. That’s valuable, of course, but it misses our current crisis which is not outer, but inner in scope. It’s time for us to take responsibility.

It’s time we take a stand toward ourselves.

(To be continued...)

Where Do I Stand?

Israel. West Bank. Israel. Gaza. Israel. “Occupied Territories.” Israel. Palestine?

Coming to the end of my trip, I thought it was time to reflect on how my position toward the conflict has evolved. I wouldn’t say my position has “changed,” necessarily, though certainly I have become far more sensitive to spin, to national narratives (aka exclusivist or selective narratives), and to the tangled web of cause and effect that will never be satisfactorily sorted out.

As of now, still about a week away from the program’s official end, here are some of my thoughts:

Although not officially a state, the Palestinian territories do comprise an entity totally distinct from Israel proper (i.e. Israel before its 1967 victory and the subsequent occupation). Having now experienced several Arab cities in the West Bank, I feel well-informed enough to make the assertion that Palestine is (de facto) and should be (de jure) a state. Again, I do not consider myself pro- either side. But after hearing as many perspectives as possible, weighing “security” against “justice” while keeping peace foremost in my mind, a quiet realism is beginning to pervade my former idealism. This is not to say that I too have given up on peace. Instead, I have come to understand that it is unrealistic to expect true empathy to emerge while present conditions remain. And present conditions, I’m sorry to say, weigh heavily in Israel’s favor politically, and heavily in the Palestinians favor morally.

That said, I also believe in Israel’s right to exist. I believe in its potential as an emergent democracy in the Middle East. I’m not sure where I stand on the notion of Israel’s identity as a “Jewish state.” This is not to say that I don’t believe in it, I just don’t know how I feel about it yet. You see, I am fundamentally conflicted about the Western compartmentalization of the world into “nation-states” in general. Without a detailed discussion, suffice it to say that I feel the system has served its purpose but is, in modern and historical form, completely incompatible with present needs and future wants. Should there be a Jewish state? What about a Muslim state? A Kurdish state? What constitutes “peoplehood” and is it synonymous with “nationhood”? If not, what differentiates them? These are all philosophical questions, of course. The reality is that Israel exists as a Jewish state, and as such, given the current conception of nation-statehood, is just as legitimate at any other state. As the situation holds, there can be no “right of return” for Palestinian refugees, no “secular, binational, one-state solution.” I do, however, feel there must be a push within Israel to clarify its murky relations between synagogue and state.

I believe there should be a Palestinian state. Israel likes to speak of “facts on the ground” (i.e. settlements, creeping annexation, etc), but Palestinians have “facts on the ground,” too. They’re called identity, lineage, language, and tradition. I believe the settlements must be stopped, most of them completely evacuated (saving perhaps several of the largest and closest to Israel), and the existing infrastructure (houses, schools, municipal buildings) left standing for new Palestinian residents.

However, after speaking to a Palestinian citizen of Israel last week, I do believe she also has a point. The formidable though unspoken Israeli policy toward the Palestinians is “divide and conquer” – though I contend that the policy wouldn’t be effective if there weren’t significance cracks in the foundations of Palestinian society that Israel could exploit. This Palestinian woman told me, I think mirroring the sentiments of many, that the two-state solution is no longer viable. With the balkanization of the Occupied Territories (Gaza completely isolated from the West Bank, Palestinians in Israel completely isolated from both Gaza and the West Bank and vice versa) there are now effectively three Palestinian entities, not one. This social and political rift will have to be remedied before Palestinian nationhood can be achieved. No unified citizenry, no nation, simple as that. We speak of Israeli-Palestinian dialogue, but there needs to be intra-community dialogue as well, especially where the Palestinians are concerned.

I believe the current Palestinian refugees residing in camps in Gaza and the West Bank need to be carefully but firmly rehabilitated. Their stories need to be told, their narratives recorded and broadcast to the world. I believe they need to feel deeply that they have been heard, recognized, and understood. And then I feel, heartless as this may seem, that they need to move on. Israel is not going anywhere and the exact land that was taken from them will never, except in rare cases, be returned. What can be returned are several priceless things, which the refugees have so far abandoned in preference for a false and limiting notion of “absolute justice.” Refugees will gain their freedom, their mobility, their full identity – not as victims, but as citizens. In gaining a future, the refugees will also, believe it or not, regain their past. For as much as they cling to it now, a past without a future is meaningless. The past bestows meaning upon the future, otherwise it is just memory.

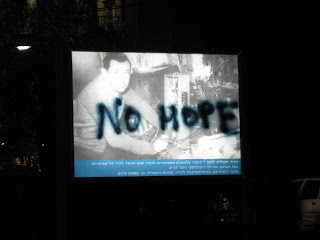

And the most interesting thing about official Palestinian statehood and citizenship? Not only will the Palestinian people themselves gain a future and regain their past, but so too will the Israelis. Currently, Israel is not just a state of Jews, it’s a state of denial and self-exile. Ironic, isn’t it? Jews flocked from all over the world to Eretz Israel, to create this Jewish homeland and claim for once a secure place at the global table. But what happened? To claim their place, the Jews had to displace others. A graffiti scrawling on the Wall said it best: “The Oppressed Become the Oppressors.” How can the Jews, once among the most rejected and persecuted people, now perpetrate similar crimes against their brother race? Recognizing and officiating the Palestinians’ national rights will allow Israel not just peace, but peace of mind...(To be continued...)

Coming to the end of my trip, I thought it was time to reflect on how my position toward the conflict has evolved. I wouldn’t say my position has “changed,” necessarily, though certainly I have become far more sensitive to spin, to national narratives (aka exclusivist or selective narratives), and to the tangled web of cause and effect that will never be satisfactorily sorted out.

As of now, still about a week away from the program’s official end, here are some of my thoughts:

Although not officially a state, the Palestinian territories do comprise an entity totally distinct from Israel proper (i.e. Israel before its 1967 victory and the subsequent occupation). Having now experienced several Arab cities in the West Bank, I feel well-informed enough to make the assertion that Palestine is (de facto) and should be (de jure) a state. Again, I do not consider myself pro- either side. But after hearing as many perspectives as possible, weighing “security” against “justice” while keeping peace foremost in my mind, a quiet realism is beginning to pervade my former idealism. This is not to say that I too have given up on peace. Instead, I have come to understand that it is unrealistic to expect true empathy to emerge while present conditions remain. And present conditions, I’m sorry to say, weigh heavily in Israel’s favor politically, and heavily in the Palestinians favor morally.

That said, I also believe in Israel’s right to exist. I believe in its potential as an emergent democracy in the Middle East. I’m not sure where I stand on the notion of Israel’s identity as a “Jewish state.” This is not to say that I don’t believe in it, I just don’t know how I feel about it yet. You see, I am fundamentally conflicted about the Western compartmentalization of the world into “nation-states” in general. Without a detailed discussion, suffice it to say that I feel the system has served its purpose but is, in modern and historical form, completely incompatible with present needs and future wants. Should there be a Jewish state? What about a Muslim state? A Kurdish state? What constitutes “peoplehood” and is it synonymous with “nationhood”? If not, what differentiates them? These are all philosophical questions, of course. The reality is that Israel exists as a Jewish state, and as such, given the current conception of nation-statehood, is just as legitimate at any other state. As the situation holds, there can be no “right of return” for Palestinian refugees, no “secular, binational, one-state solution.” I do, however, feel there must be a push within Israel to clarify its murky relations between synagogue and state.

I believe there should be a Palestinian state. Israel likes to speak of “facts on the ground” (i.e. settlements, creeping annexation, etc), but Palestinians have “facts on the ground,” too. They’re called identity, lineage, language, and tradition. I believe the settlements must be stopped, most of them completely evacuated (saving perhaps several of the largest and closest to Israel), and the existing infrastructure (houses, schools, municipal buildings) left standing for new Palestinian residents.

However, after speaking to a Palestinian citizen of Israel last week, I do believe she also has a point. The formidable though unspoken Israeli policy toward the Palestinians is “divide and conquer” – though I contend that the policy wouldn’t be effective if there weren’t significance cracks in the foundations of Palestinian society that Israel could exploit. This Palestinian woman told me, I think mirroring the sentiments of many, that the two-state solution is no longer viable. With the balkanization of the Occupied Territories (Gaza completely isolated from the West Bank, Palestinians in Israel completely isolated from both Gaza and the West Bank and vice versa) there are now effectively three Palestinian entities, not one. This social and political rift will have to be remedied before Palestinian nationhood can be achieved. No unified citizenry, no nation, simple as that. We speak of Israeli-Palestinian dialogue, but there needs to be intra-community dialogue as well, especially where the Palestinians are concerned.

I believe the current Palestinian refugees residing in camps in Gaza and the West Bank need to be carefully but firmly rehabilitated. Their stories need to be told, their narratives recorded and broadcast to the world. I believe they need to feel deeply that they have been heard, recognized, and understood. And then I feel, heartless as this may seem, that they need to move on. Israel is not going anywhere and the exact land that was taken from them will never, except in rare cases, be returned. What can be returned are several priceless things, which the refugees have so far abandoned in preference for a false and limiting notion of “absolute justice.” Refugees will gain their freedom, their mobility, their full identity – not as victims, but as citizens. In gaining a future, the refugees will also, believe it or not, regain their past. For as much as they cling to it now, a past without a future is meaningless. The past bestows meaning upon the future, otherwise it is just memory.

And the most interesting thing about official Palestinian statehood and citizenship? Not only will the Palestinian people themselves gain a future and regain their past, but so too will the Israelis. Currently, Israel is not just a state of Jews, it’s a state of denial and self-exile. Ironic, isn’t it? Jews flocked from all over the world to Eretz Israel, to create this Jewish homeland and claim for once a secure place at the global table. But what happened? To claim their place, the Jews had to displace others. A graffiti scrawling on the Wall said it best: “The Oppressed Become the Oppressors.” How can the Jews, once among the most rejected and persecuted people, now perpetrate similar crimes against their brother race? Recognizing and officiating the Palestinians’ national rights will allow Israel not just peace, but peace of mind...(To be continued...)

Thursday, July 16, 2009

Has It Really Been Six Weeks?

What have I learned from my internship experience? Where do I begin?

First, I’ve learned what Ashoka is and what it is not. After an interview for a potential fellow the other day, Nir asked me, “So, is she Ashoka material or not?” Now I’m always one to weigh the pros and cons, to give detailed analyses, to say “one the one hand…but on the other…” and continue like this for some time before making up my mind. But Nir pressed me. “I want a ‘yes’ or ‘no.’” At heart, I had been impressed by her passion but not her creativity. The idea she presented was nothing new, but rather the first time an Israeli environmental organization sat down with key energy stakeholders (like Israel Electric Corporation – IEC) to try to collaborate on smarter energy policy. The idea of energy efficiency and lobbying to influence policymakers is pretty standard, though nevertheless extremely important. Nir cut to the chase: “She’s not for Ashoka because she doesn’t really have a new idea. Her work is about influencing business leaders and policy makers, but Ashoka’s mission is to fund innovation for the social good. If there’s no innovation, Ashoka can’t fund a fellow no matter how important their work is. That’s our niche and our mission.”

And I respect that because, though other organizations have now taken up the cause of social entrepreneuring, none is as experienced, thorough, or successful as Ashoka. Most organizations stick with the tried-and-true since they lack Ashoka’s method of discerning which ideas will work and which are mere pipe dreams.

Telling me to go with my gut was an important lesson Nir taught me. Sometimes more information, research and analysis can’t replace your own instinct and intuition. Ashoka is all about individuals and relationships. But it’s also about widespread, systemic change. But how can one person change a system? It happens, of course. But we are taught that it happens very rarely and only then in specific situations. Ashoka challenges such conventional wisdom (indeed, Ashoka is all about challenges conventions).

Instead of relying on governments, businesses, and bureaucracies that operate at such a high level individuals are affected but remain untouched, Ashoka turns the equation on its head. Individuals can affect systems, but it depends on the kind of individual. Ashoka’s “social entrepreneur” is someone who possesses unique capabilities – passionate, creative, conscientious, systematic, dogged, ethical. They are open-minded but also relentless in their pursuit of a dream, but more importantly in its realization, implementation and replication. Ashoka doesn’t really care about application forms or impeccable résumés. What matters more are detailed action plans, financial records, references asserting moral fiber. You will never bore an Ashoka representative by giving specifics. Rather, specifics are constantly being sought, more specific specifics asked for.

My job this summer has been to compile a number of profiles for the first cadre of Ashoka Israel’s potential fellows. Each profile must contain the following information (in addition to basics like name, country of origin, organization, sector, target population, etc.): (1) an analysis of the new idea – is it practical? who else is doing something similar? what makes this approach unique? does it change or build upon other work in the field? etc. (2) an analysis of the problem to be addressed – why have others failed to solve this problem? how widespread is it? whom does it effect? what is its political, social, cultural, economic background? etc. (3) an analysis of the entrepreneur’s strategy – how are resources being mobilized? is there a vision for national impact? how does the project progress from its pilot stage to its institutionalization? who are the other major players? does the strategy deal with causes or mere symptoms of the problem? etc. (4) an analysis of the person – what is their family, educational, and professional background? what other activities/achievements show an inbuilt entrepreneurial nature? what struggles has he/she overcome and how? etc. Of course, there are many more questions each profile must answer, but this gives you the gist.

For a while, I wasn’t quite sure how important these profiles would be. I mean, am I just collating a lot of interesting but easily-accessible facts (via websites, interviews, etc.)? Nir put that concern to rest quickly by presenting me with an Ashoka handbook detailing the search and selection process of potential fellows. It consists of six very rigorous steps: (1) nomination; (2) preliminary screening and interview; (3) profile writing; (4) second opinion review; (5) selection panel; (6) international board approval.

Nir is, in many ways, a one-man show, spearheading steps 1, 2, 4 and 5 (3 is for me). Of course, he has an extensive network of nominators within Israel – business leaders, professors, friends, entrepreneurs, health professionals, environmental activists, artists, teachers, etc. – all of whom flag potential candidates. It is then Nir’s job, as Ashoka Israel’s country representative, to interview the person. If he feels both instinctually and informationally convinced, he continues the interview process. Once he is relatively sure of a candidate’s success before the selection panel (coming up in August), the task is turned over to me. Not only do I gather information for the profile, but I have to analyze the information in light of Ashoka’s rigorous standards.

Two judgment calls are particularly tough. First, is this new idea really new? To find that out, I must study the playing field, determine if other Ashoka fellows have attempted something similar elsewhere, or if another NGO is pursuing a parallel course. Second, if the idea is indeed new, how viable is it? This is much harder to discern sometimes, especially if the candidate is working in a field of which I has little direct knowledge. Usually, the more detailed the candidate’s plan of action and the more past results they have documented both qualitatively and quantitatively, the more viable their strategy seems.

I still didn’t realize the importance of a well-researched, well-written profile, however, until Nir told me that the profile is the only thing the Board will have to go on since they will not be able to actually interview the candidate. At this point, I felt a bit like I was writing someone’s college entrance essay for them. Then, the Ashoka handbook Nir gave me had this to say on the subject of profiles:

“Everyone who has ever worked at Ashoka can agree on two basic issues. The first is that, in order to elect Fellows of the highest quality, we must be able to gather all relevant information and impressions about the person and their project, then present this material in a compelling and comprehensive manner in their profile. The second point of consensus is that profile-writing has proven to be a very difficult, expensive and time-consuming process for the institution, causing frustration at every level from country representatives to Board members...”

Nice, I thought. I’m helping Nir with a task that is necessary to elect fellows of the “highest quality.” Profiles should be “comprehensive and compelling,” but such a requirement has proven “difficult, expensive, and time-consuming.” Difficult and time-consuming I can definitely attest to. Expensive? Well, fortunately for Nir, my services are gratis.

At the same time as I am learning the intricacies of a well-crafted profile, I am also learning about Nir’s job. Since he does not have an official Ashoka office yet (though he plans to rent one soon), he, like me, is reliant on his own motivation, his contacts, his computer, and his ability to wear several hats at once. Despite his lack of colleagues (except me!), Nir meets a lot of people. Not only does he travel the country meeting potential candidates, he strengthens and expands his network constantly. All the events I’ve attended with Nir have been places to network, to meet and greet and possibly connect with someone whose professional services or, in the case of donors, monetary resources coincide with compatible interests.

In the short time I’ve been in Israel, Nir has been to London, New York, and DC in a constant process of outreach and interaction. Within Israel, he has traveled to the Negev, Nazareth, Be’er Sheva, and Jerusalem (as far as I know), all to meet and interview candidates, see their organizations – in sum, to ascertain from the mind, heart, and gut whether a person is certifiable “changemaker” or not (Product plug! But it’s free and a new website you really should check out. Ashoka’s new “Changemakers” platform: http://www.changemakers.com).

On the personal front, I don’t know how much I’ve actually learned, since I knew before I came to Israel that I work best on my own, that I appreciate the flexibility of making my own schedule, that I am always most productive when treated as an equal rather than as a corporate nonentity (as most interns are viewed). While Nir clearly is the one giving the orders, he always emphasizes the collegial aspect of our association (for instance, he introduces me as his “summer associate”). It’s a good policy in general (not to mention making business relations far more comfortable and fun), since it raises my stake in Ashoka Israel, making me feel personally invested in its upcoming launch.

Today I think I’m going to meet one of our most successful candidates – a man named Shai Reshef whose “new idea” is to create the first free online university. Here’s a link to a New York Times article about him http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/26/education/26university.html and an ABC news clip: http://76.12.20.118/abc/abc.html.

In sum, I have not yet been disillusioned by Ashoka. And that, more than anything, was a learning experience well worth having.

First, I’ve learned what Ashoka is and what it is not. After an interview for a potential fellow the other day, Nir asked me, “So, is she Ashoka material or not?” Now I’m always one to weigh the pros and cons, to give detailed analyses, to say “one the one hand…but on the other…” and continue like this for some time before making up my mind. But Nir pressed me. “I want a ‘yes’ or ‘no.’” At heart, I had been impressed by her passion but not her creativity. The idea she presented was nothing new, but rather the first time an Israeli environmental organization sat down with key energy stakeholders (like Israel Electric Corporation – IEC) to try to collaborate on smarter energy policy. The idea of energy efficiency and lobbying to influence policymakers is pretty standard, though nevertheless extremely important. Nir cut to the chase: “She’s not for Ashoka because she doesn’t really have a new idea. Her work is about influencing business leaders and policy makers, but Ashoka’s mission is to fund innovation for the social good. If there’s no innovation, Ashoka can’t fund a fellow no matter how important their work is. That’s our niche and our mission.”

And I respect that because, though other organizations have now taken up the cause of social entrepreneuring, none is as experienced, thorough, or successful as Ashoka. Most organizations stick with the tried-and-true since they lack Ashoka’s method of discerning which ideas will work and which are mere pipe dreams.

Telling me to go with my gut was an important lesson Nir taught me. Sometimes more information, research and analysis can’t replace your own instinct and intuition. Ashoka is all about individuals and relationships. But it’s also about widespread, systemic change. But how can one person change a system? It happens, of course. But we are taught that it happens very rarely and only then in specific situations. Ashoka challenges such conventional wisdom (indeed, Ashoka is all about challenges conventions).

Instead of relying on governments, businesses, and bureaucracies that operate at such a high level individuals are affected but remain untouched, Ashoka turns the equation on its head. Individuals can affect systems, but it depends on the kind of individual. Ashoka’s “social entrepreneur” is someone who possesses unique capabilities – passionate, creative, conscientious, systematic, dogged, ethical. They are open-minded but also relentless in their pursuit of a dream, but more importantly in its realization, implementation and replication. Ashoka doesn’t really care about application forms or impeccable résumés. What matters more are detailed action plans, financial records, references asserting moral fiber. You will never bore an Ashoka representative by giving specifics. Rather, specifics are constantly being sought, more specific specifics asked for.

My job this summer has been to compile a number of profiles for the first cadre of Ashoka Israel’s potential fellows. Each profile must contain the following information (in addition to basics like name, country of origin, organization, sector, target population, etc.): (1) an analysis of the new idea – is it practical? who else is doing something similar? what makes this approach unique? does it change or build upon other work in the field? etc. (2) an analysis of the problem to be addressed – why have others failed to solve this problem? how widespread is it? whom does it effect? what is its political, social, cultural, economic background? etc. (3) an analysis of the entrepreneur’s strategy – how are resources being mobilized? is there a vision for national impact? how does the project progress from its pilot stage to its institutionalization? who are the other major players? does the strategy deal with causes or mere symptoms of the problem? etc. (4) an analysis of the person – what is their family, educational, and professional background? what other activities/achievements show an inbuilt entrepreneurial nature? what struggles has he/she overcome and how? etc. Of course, there are many more questions each profile must answer, but this gives you the gist.

For a while, I wasn’t quite sure how important these profiles would be. I mean, am I just collating a lot of interesting but easily-accessible facts (via websites, interviews, etc.)? Nir put that concern to rest quickly by presenting me with an Ashoka handbook detailing the search and selection process of potential fellows. It consists of six very rigorous steps: (1) nomination; (2) preliminary screening and interview; (3) profile writing; (4) second opinion review; (5) selection panel; (6) international board approval.

Nir is, in many ways, a one-man show, spearheading steps 1, 2, 4 and 5 (3 is for me). Of course, he has an extensive network of nominators within Israel – business leaders, professors, friends, entrepreneurs, health professionals, environmental activists, artists, teachers, etc. – all of whom flag potential candidates. It is then Nir’s job, as Ashoka Israel’s country representative, to interview the person. If he feels both instinctually and informationally convinced, he continues the interview process. Once he is relatively sure of a candidate’s success before the selection panel (coming up in August), the task is turned over to me. Not only do I gather information for the profile, but I have to analyze the information in light of Ashoka’s rigorous standards.

Two judgment calls are particularly tough. First, is this new idea really new? To find that out, I must study the playing field, determine if other Ashoka fellows have attempted something similar elsewhere, or if another NGO is pursuing a parallel course. Second, if the idea is indeed new, how viable is it? This is much harder to discern sometimes, especially if the candidate is working in a field of which I has little direct knowledge. Usually, the more detailed the candidate’s plan of action and the more past results they have documented both qualitatively and quantitatively, the more viable their strategy seems.

I still didn’t realize the importance of a well-researched, well-written profile, however, until Nir told me that the profile is the only thing the Board will have to go on since they will not be able to actually interview the candidate. At this point, I felt a bit like I was writing someone’s college entrance essay for them. Then, the Ashoka handbook Nir gave me had this to say on the subject of profiles:

“Everyone who has ever worked at Ashoka can agree on two basic issues. The first is that, in order to elect Fellows of the highest quality, we must be able to gather all relevant information and impressions about the person and their project, then present this material in a compelling and comprehensive manner in their profile. The second point of consensus is that profile-writing has proven to be a very difficult, expensive and time-consuming process for the institution, causing frustration at every level from country representatives to Board members...”

Nice, I thought. I’m helping Nir with a task that is necessary to elect fellows of the “highest quality.” Profiles should be “comprehensive and compelling,” but such a requirement has proven “difficult, expensive, and time-consuming.” Difficult and time-consuming I can definitely attest to. Expensive? Well, fortunately for Nir, my services are gratis.

At the same time as I am learning the intricacies of a well-crafted profile, I am also learning about Nir’s job. Since he does not have an official Ashoka office yet (though he plans to rent one soon), he, like me, is reliant on his own motivation, his contacts, his computer, and his ability to wear several hats at once. Despite his lack of colleagues (except me!), Nir meets a lot of people. Not only does he travel the country meeting potential candidates, he strengthens and expands his network constantly. All the events I’ve attended with Nir have been places to network, to meet and greet and possibly connect with someone whose professional services or, in the case of donors, monetary resources coincide with compatible interests.

In the short time I’ve been in Israel, Nir has been to London, New York, and DC in a constant process of outreach and interaction. Within Israel, he has traveled to the Negev, Nazareth, Be’er Sheva, and Jerusalem (as far as I know), all to meet and interview candidates, see their organizations – in sum, to ascertain from the mind, heart, and gut whether a person is certifiable “changemaker” or not (Product plug! But it’s free and a new website you really should check out. Ashoka’s new “Changemakers” platform: http://www.changemakers.com).

On the personal front, I don’t know how much I’ve actually learned, since I knew before I came to Israel that I work best on my own, that I appreciate the flexibility of making my own schedule, that I am always most productive when treated as an equal rather than as a corporate nonentity (as most interns are viewed). While Nir clearly is the one giving the orders, he always emphasizes the collegial aspect of our association (for instance, he introduces me as his “summer associate”). It’s a good policy in general (not to mention making business relations far more comfortable and fun), since it raises my stake in Ashoka Israel, making me feel personally invested in its upcoming launch.

Today I think I’m going to meet one of our most successful candidates – a man named Shai Reshef whose “new idea” is to create the first free online university. Here’s a link to a New York Times article about him http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/26/education/26university.html and an ABC news clip: http://76.12.20.118/abc/abc.html.

In sum, I have not yet been disillusioned by Ashoka. And that, more than anything, was a learning experience well worth having.

Wednesday, July 15, 2009

Monday, July 13, 2009

When Will the Caged Bird Fly?

Yesterday was Bethlehem. Along with Ramallah, it was probably one of the most contrasting and provocative experiences of my trip. (And now my blog title "Slouching through Bethlehem" has literal, as well as figurative meaning.)

Waiting at the checkpoints in the hot, hot sun; watching Israeli soldiers treat Arabs with disdain; listening to yet another story of “the Israelis turned the water off today, and yesterday, and the day before...” – it was hard not to empathize with the Palestinians, even if I knew too that the 1948 refugees are partially victims of their own despair.

What do I mean? Well, the first refugee camp I visited was Qalandia, on the outskirts of Ramallah. Our guide, Ahmad Naf’e, was a native of the area and knew the camps and their denizens well. He told us – later to be reinforced by other anecdotes and personal encounters – that the residents of Palestinian refugee camps (to be differentiated from the Lebanese camps, which are a different story) actually choose to stay there. I repeat, they CHOOSE to stay in the camps despite the fact that there are other places, nicer, cleaner, more hopeful places, for them to live.

Now, to someone outside the Palestinian worldview, this self-imposed imprisonment seems counterintuitive. Why would anyone choose to live in a refugee camp? To understand this, one must first understand the level of helplessness and victimization Palestinians feel – and in many cases, rightfully so. Violent protests are ruthlessly cut down by Israeli forces, while nonviolent protests (marches, demonstrations, campaigns) are ignored. The most powerful expression of Palestinian nationalism and pride is their presence. They have come to understand that their mere presence is a thorn in the side of Israel. Since Israel remains unalterably opposed to the “right of return,” and at the same time seemingly opposed to a “two-state solution,” what else remains for displaced Palestinians to do but to stay exactly where they are, in their camps, as a form of silent and terrible (for them) protest against Israeli occupation?

This is the rationale. This is the reason tens of thousands of Palestinians live in unlocked prisons, gated but freely accessible to the rest of society, ringed with barbed wire in a silent scream against injustice. You drove us from our homes! they shout without words. You took away our land. You killed our families. You treat us like criminals. You deny our claims to this homeland which is ours just as much as it is yours (or, in their eyes, more so). But this demand for absolute justice, this refusal to move on – all this comes at great cost. I feel that their claims might be more reasonable, their idea of justice modified, if the Israelis and the rest of the world really and truly heard their story. Heard it and legitimized it, not treated it (as they have thus far) with token regard.

To go to the camps is to visit a world of tangible but unutterable strangulation. The scream which goes unvoiced is unheard but not unfelt. Indeed, it is omnipresent. In Bethlehem yesterday, I went to the home of Paula’s host family, who live in the Assa refugee camp. The home itself was not small, dirty and cramped as I had envisioned. It was a bit dirty yes, but this is the Middle East – Israel’s dirty, everything’s dirty. The house was in fact quite large, with adequate living space for four people (though a bit cramped for six – the two additions being our summer interns). Symbols of the conflict were everywhere. On one wall was a map showing Palestine, but no Israel. Other photographs showed a grandmother who had been killed at an Israeli checkpoint and Islamic holy places in Jerusalem. The young woman of the house had never been to Israel, except when she was very young. Outside the home, Israel’s “security wall” is a constant reminder of oppression, wending its way around the camp’s outskirts, a stone’s throw (forgive the analogy) from schools and families. You can almost feel the air being sucked out of its surroundings. Everything becomes heavy in the presence of the wall, ominous, devoid of energy, purpose, vitality. The graffiti art is the only thing that hints at humanization, at humor and the irrepressible urge to speak truth to power. And then there are children. The children, thank God, are still wonderfully intense.

Paula works with an organization that attempts to raise awareness of refugee life and Palestinian culture, as well as giving Palestinian children a positive outlet and diversion from the conflict. It is located in the Aida refugee camp. She showed us around the building, which houses classrooms, a small library, kitchen, a larger auditorium, an audio-visual room with computers (where Palestinians are using the medium of film to document their lives and impressions), and several offices. In the auditorium, a large group of children was standing is a circle. One little boy was leading them in a very energetic rendition of all the different noises animals make. Truly, he was the most dynamic presence in the place and he can’t have been older than nine or ten. Tweet tweet tweet! Peep peep peep! Coo coo coo! Moo moo moooooooo! And all the children echoed him.

In addition to the camps, Paula told us about the tensions between Christians and Muslims in Bethlehem – how the Muslims feel themselves to be on better terms with the Christians than the Christians feel about their relations with the Muslims. The difference between the Arab shouk (marketplace) and Christian quarter was also stark. The streets of the Christian quarter could hardly have been cleaner or quieter, the buildings pristine. The Muslim streets, in contrast, were filthy, noisy and crowded, filled with vendors and oncoming cars. Paula said that generally the Christians are better off than their Muslim neighbors, although ironically (for a city historically associated with Christ) they are now a minority of the population.

When I typed “Christians in Bethlehem” into the Google search box, a Jerusalem Post article from 2007 popped up: “A number of Christian families have finally decided to break their silence and talk openly about what they describe as Muslim persecution of the Christian minority in this city.” In 2006, the BBC reported: “The little town of Bethlehem is perhaps more associated with Christianity than any other place in the world. But now there are fears that soon it could be home to hardly any Christians at all” due to increased security hassles and the Israeli wall. Nearly every search result was some variation of “Christian minority fleeing persecution” in Bethlehem. When I reversed the search, typing “Muslims in Bethlehem,” I got a similar picture. Results proclaimed “Muslims persecuting Bethlehem’s Christians.” But everything dates back to 2005 or 2006, so I wonder what a more current analysis would find.

Until yesterday, I had been planning to visit internships in Nazareth, but now I’m feeling the need to spend one more day in the West Bank before I go home. Maybe I’ll go back to Ramallah...

Waiting at the checkpoints in the hot, hot sun; watching Israeli soldiers treat Arabs with disdain; listening to yet another story of “the Israelis turned the water off today, and yesterday, and the day before...” – it was hard not to empathize with the Palestinians, even if I knew too that the 1948 refugees are partially victims of their own despair.

What do I mean? Well, the first refugee camp I visited was Qalandia, on the outskirts of Ramallah. Our guide, Ahmad Naf’e, was a native of the area and knew the camps and their denizens well. He told us – later to be reinforced by other anecdotes and personal encounters – that the residents of Palestinian refugee camps (to be differentiated from the Lebanese camps, which are a different story) actually choose to stay there. I repeat, they CHOOSE to stay in the camps despite the fact that there are other places, nicer, cleaner, more hopeful places, for them to live.

Now, to someone outside the Palestinian worldview, this self-imposed imprisonment seems counterintuitive. Why would anyone choose to live in a refugee camp? To understand this, one must first understand the level of helplessness and victimization Palestinians feel – and in many cases, rightfully so. Violent protests are ruthlessly cut down by Israeli forces, while nonviolent protests (marches, demonstrations, campaigns) are ignored. The most powerful expression of Palestinian nationalism and pride is their presence. They have come to understand that their mere presence is a thorn in the side of Israel. Since Israel remains unalterably opposed to the “right of return,” and at the same time seemingly opposed to a “two-state solution,” what else remains for displaced Palestinians to do but to stay exactly where they are, in their camps, as a form of silent and terrible (for them) protest against Israeli occupation?

This is the rationale. This is the reason tens of thousands of Palestinians live in unlocked prisons, gated but freely accessible to the rest of society, ringed with barbed wire in a silent scream against injustice. You drove us from our homes! they shout without words. You took away our land. You killed our families. You treat us like criminals. You deny our claims to this homeland which is ours just as much as it is yours (or, in their eyes, more so). But this demand for absolute justice, this refusal to move on – all this comes at great cost. I feel that their claims might be more reasonable, their idea of justice modified, if the Israelis and the rest of the world really and truly heard their story. Heard it and legitimized it, not treated it (as they have thus far) with token regard.